"Nature is not a place to visit; it is home." -Gary Snyder

Miguel Provencio shows a mountain yellow-legged frog to freedom.

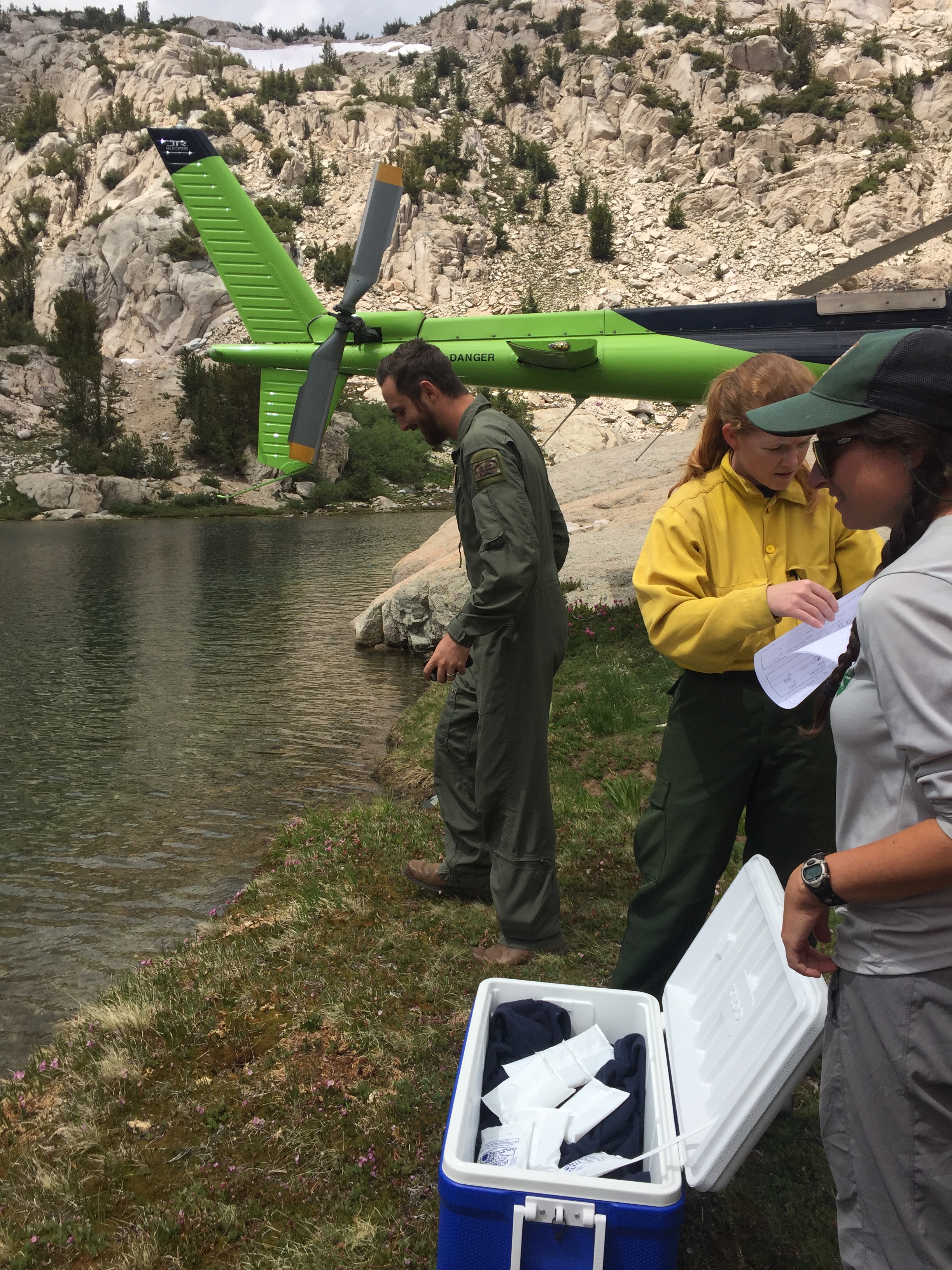

This week, we hiked to the site where my field partner and I will spend our next three 10-day trips. This basin is very different from the last, and about 400 feet lower, with more trees and fewer frogs. Having been hit by the amphibian chytrid fungus, the mountain yellow-legged frog populations here are persisting at a very low level. Frogs are even being flown up to higher fishless lakes in the basin to try to bolster their numbers, and this basin harbors one of those lakes. This week, 25 frogs were brought from the San Francisco Zoo, via Prius, to the Ash Mountain helibase of Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park, and then flown by helicopter to our site. There is nothing quite like releasing animals back into their native home, in the hopes that they will persist into a better future. (More images are available in the gallery at the bottom of this post).

Mount Lyell salamander, Hydromantes platycephalus

Earlier in the week, we packed our sleeping bags and hiked up a side drainage in search of the rare, legendary Mt. Lyell salamander. This species belongs to the family of salamanders without lungs (Plethodontidae). What makes them extra special is that they are found only in seeps on cliff faces and in granite talus from 4,000 to 12,000 feet in elevation. They have even been observed on snow! Once we reached the granite bench where we would be sleeping, we watched the sun set over the basin while we waited for nightfall. Then we hiked up to the first seeps we could find. After some searching through the darkly colored cracks in the rock where the water trickled and the plants grew in miniature, there they were--two beautiful grey Hydromantes platycephalus, their skin perfectly matching the wet rock they clung to. One of them made a break for it and slowly crawled up the seep away from us. The other--larger--hunkered down in place. We stood on our toes to get a better view, balancing carefully on the edges of the wet, mossy rocks beneath our feet. Afterward, we stopped to watch the Milky Way perfectly reflected in a glassy lake like an inky underworld. Back at our granite slab overlooking the basin, we fell asleep under the final showing of the Perseid meteor shower.

Again, the wildflowers were stunning, giving it all they've got in the brief window of High Sierra summer. They sprout up from the most unlikely places--between and under rocks, in the interstices of cliff faces. I was scrambling across some cliffs to reach a stretch of lake shore when the most perfect columbine I had ever seen exploded in front of me. It was flawless--the flowers had just opened, and the next blossoms in line were hanging at exact angles from the blooms. I was fairly far from the nearest trail and alone--I may be the only human who got to see that perfect flower.

It's no wonder that John Muir's descriptions of Sierra Nevada natural history read like devotional poems--here, nature has a way of reaching into a person like nowhere else.